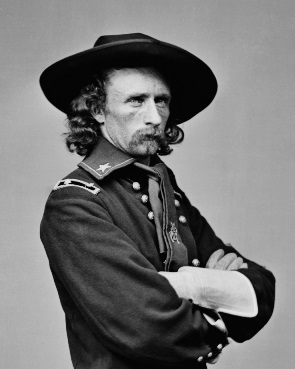

Almost 150 years ago, on hot and dusty Sunday afternoon 25 June 1876, Brevet Major General, Lt Col George Armstrong Custer led five companies of his battalion into a buzz saw of Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors in the Battle of the Little Big Horn, or the Greasy Grass, in what was then, the territory of Montana. In a fight that lasted less than an hour, every man of those five companies lay dead, (save for bugler, and recent Italian immigrant Giovanni Martini/John Martin, who was sent off by Custer at the start of the fight, with a hastily scribbled message to Captain Frederick Benteen, “Come on—Big village—Be quick—bring packs.”) some 210 soldiers, scouts and civilians.

Some years ago, back when I was in the land of basic cable, the History Channel had a program where a “historical” period film was shown, and then followed by a panel discussion of historians with the theme of “Is it history, or is it Hollywood?”

I don’t remember much specific of any of those discussions. But anyone thinking, or expecting a movie to accurately depict historical events in a dramatic film, has a long way to go in understanding that historical facts and the motives and/or needs of a dramatist – let alone the need to make the money for the people putting up the money. Often times events may be compressed, switched around on the timeline, individual participants combined into single characters, and lots of shit just plain made up.

For good or ill, the history is often just a starting point for most “historical” films. You have to tell a story that people want to watch. And there needs to be a reason to tell that story. The based on a “true” story may just be a jumping off point to concoct whatever the scenarist decides to write.

“Based on a true story” it may be, but that doesn’t mean that 95 percent of what’s on the screen isn’t entirely made up.

To paraphrase Armando Iannucci, the writer – director of The Death of Stalin (2017) – “I wasn’t making a documentary.” No he was making a very black satirical comedy on the historically based political situation and characters immediately before and after the death of Josef Stalin in the Soviet Union. Many of the basic events, character depictions, and even detailed bits are (to my limited research) are generally correct, or at least apocryphally. But he certainly compressed some events, and made some shit up. He is presenting/telling a story. Whether you liked it or not should not hang only on just how “accurate” it is to the “true story.” If it does, then a whole lot of historically based movies are going to get a fail.

I recently watched a YouTube video where the creator spent over thirty-minutes declaiming how much he loved Braveheart (1995) while simultaneously trashing it for all of its historically inaccuracies. Even a modicum of research into William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, and Edward I proves how much of Braveheart the writer and the director changed, and just made up. A lot.

You want real “history,” real “facts,” read a book on the subject – better yet, several books. Research. Different writers will present the same event with different view points of view of the same facts, or selection of facts, not to mention interpretation of facts. There also may be differing sets of “facts” from primary sources. Plus writers have their own opinions/slants, and it depends on the individual authors as to what and how much of the material is affected by particular viewpoint. Historians are not supposed to do that, but they are people. And you know how people can be.

I may be preaching to the choir, but you get the point.

American history (forgetting world history for now) has a whole stock company of usual suspects and events that have been endlessly portrayed, or form a background to the narrative. How many times have the likes of Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Wyatt Earp, Al Capone, and John Dillinger been essayed in films? Even the most “accurate” of these films are pretty far from truth, and most are not within a thousand miles. And the reality usually doesn’t contain an ounce of real romance.

Which brings me back to the subject of this rambling rumination: that controversial, vainglorious golden boy, Brevet Major General, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer.

Custer has not been essayed in movies nearly as much as some of the persons named above, but his stock in the historical/public opinion market has certain changed wildly.

The June 1876 battle events are much more complicated than what I described above. The battle raged off and on for over three days, the 25th through the 27th. The 7th Cavalry was not wiped out. Custer had split his command into four pieces: a battalion of three companies under Major Marcus Reno, a battalion of three companies under Captain Frederick Benteen, and a pack train of one company. The 7th Cavalry regiment consisted of around 680 men. There were about 260 casualties killed. How many Indian American warriors were there? That varies depending on who you read – anywhere from 1500-3000. Their casualties were significantly less – an estimated 160 (?.) One maybe can not entirely blame Custer for the loss of his men. (But he was in a big damned hurry. He was afraid the prey would get away from him. Irony.) Such a massive encampment of Plains Indians (an estimated population of 10 – 13,000 people) had never been known of before. All of the numbers quoted above vary from source to source. But. You could say that Custer stumbled into legend.

So it began. Regardless of the “facts,” the Custer myth/legend was set in motion. He was already a nationally known figure. The Little Bighorn just ensured that he would be remembered long after his death.

The politics and series of connected events that led up to Custer even being in that place, at that time are considerable. But. It is safe to say that the fight at the Little Big Horn, while a disaster was, strategically, rather insignificant. Casualties in many Civil War battles were in the thousands. It certainly did not slow the inevitability of crushing of the freedom and life style of Plains Indians. It only accelerated it. Its importance lay in the symbolism of brave white America against the vicious savages. That Custer had been out-generalled by Chief Crazy Horse and Chief Gall was never a consideration.

1876 was the Centennial year for the United States. The news broke pretty much right on the fourth of July. It was a massive shock and considered a national tragedy. There was a national outcry for blood vengeance. Before it was over the Americans Plains Indians paid more than ten-fold for the Custer fight.

Since 1876, the Little Big Horn battle has been depicted in countless paintings and illustrations. Hundreds, and hundreds of books on the battle have been written (and continue to be written.) Historians continue to research and traipse around the battle site searching for fragments. But much of what happened on that June afternoon in 1876 is still only a matter of speculation. There are many recorded recollections from Indian participants, but of course, none from the opposite side. Then what about Reno and Benteen? That again depends on your interpretation of other interpretations and what you wish to believe. I doubt Custer could have been saved.

In succeeding decades the view/interpretations of Custer changes – ranging from the dashing and brave cavalry leader to an arrogant, foolhardy, self-promoting glory seeker. Both views are probably somewhat correct. Although my view goes more with the latter.

Custer’s widow Elizabeth “Libbie” Custer was a fierce defender/custodian of her husband. She did public lectures and wrote several books, that are considered relatively accurate, but heavily slanted to glorify her husband. (And no, I have yet to read them.) Libbie lived until 1933, well over a half-century after event keeping the Custer legend alive.

So. To the point of this whole ramble: the depiction of George Armstrong Custer in the movies. In particular how the portrayal of Custer evolved in the movies/popular culture. But I am keeping myself (mostly) restrained to three Custer portrayals: Francis Ford in Custer’s Last Fight (1912); Errol Flynn in They Died with Their Boots On (1941) and Richard Mulligan in Little Big Man (1971.)

The first, as far as my research shows, cinematic re-telling of the Greasy Grass/Little Bighorn fight is the short On the Little Big Horn, or Custer’s Last Stand produced by William Selig in 1909. But I can find nothing other than a listing on IMDB, and a few mentions elsewhere.

The 1912 Thomas Ince production of Custer’s Last Fight, directed and starring John Ford’s big brother Francis Ford as “Yellow Hair” himself, is often sited as the first Custer film. (Ince is the only one credited on the film, but he routinely stole credit for all his films.)

Produced just 35 years after the event, and with Libbie Custer still very much alive, this version doesn’t stray from the Custer hero legend. The original 1912 film ran around 30 minutes long, it was re-released with different title cards and added scenes in 1925 (the fifty year anniversary was in the offing) at 54 minutes. The version(s) available on YouTube runs a little over 40 minutes. I don’t what all was added, except an epilogue of sorts about the Ghost Dance and death of Sitting Bull that feels tacked on.

The film itself is rather accurate in a lot of it’s historical detail (It’s almost a docudrama in that provides event detail and it depicts incident with little to no character development.) albeit slanted most heavily in favor of the “white man” and his viewpoint. Custer is the brave “Indian fighter” and the Indians are conniving devils. The title cards leave no doubt as to which side they’re on.

That said, most if not all of the Indians are seemingly portrayed by real Native Americans. (Some are supposedly veterans of the 1876 fight.) And, more factual historical background concerning some of the political motivations and military campaign are provided than are available in either of the two other prime portrayals of Custer I want to examine. The Custer in Custer’s Last Fight is no more than a historical cipher.

There are a number of Custer film sightings in the teens, twenties, and thirties where is the main focus, or a major supporting character – including Cecil B. DeMille’s highly entertaining, and most highly fictionalized The Plainsman (1936.) Custer was still portrayed mostly in a positive light in these films.

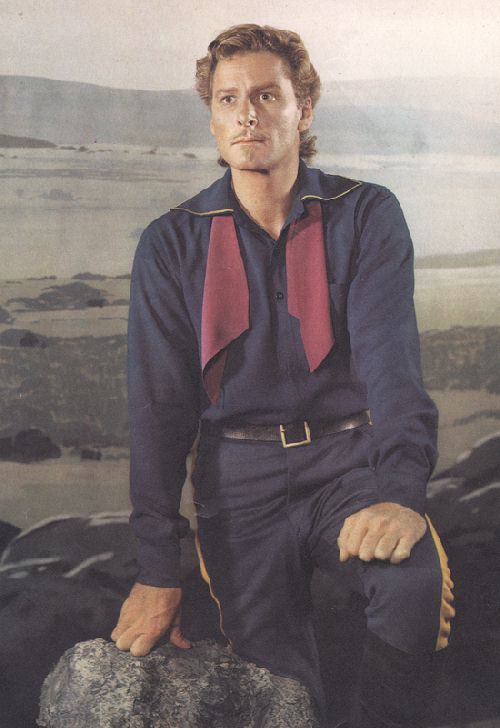

Then came 1941. Warner Brothers produced They Died with Their Boots On. It premiered 20 November 1941, and went into general release on 01 January 1942. It purports to portray the life of George Armstrong Custer from his entry into West Point in 1857 until his ultimate end in 1876. To say that it gets almost every single fact wrong is not an understatement. A whole-spun fictional take, with a few facts strewn about is probably the best way to describe Boots. Or, a “towering pack of lies” that would “explode the heads” of any real historian, as one writer described the movie.

Boots opens with Custer’s making an amusing entry into West Point, where he immediately gets into trouble. He meets cute with Elizabeth “Libbie” Bacon (Olivia deHavilland,) piles up demerits and graduates at the bottom of his class when the Civil War breaks out. Custer then charms/cons General Winfield Scott (Sydney Greenstreet) into giving him a cavalry command, then disobeys orders, saves the day and becomes a hero. Next he accidentally becomes a general, defeats J.E.B. Stuart at Gettysburg, again saving the day. Along the way he makes some personal enemies, gets married to Libbie, leaves the army, gets bored and begins drinking (Custer was a teetotaler and never drank,) rejoins the army and is sent out west to lead the Seventh Cavalry. There Custer meets cute with Crazy Horse (Anthony Quinn,) and promises to be the Indian’s friend. Meanwhile he tangles with his old enemies who are now the Indian Commissioner and a crooked businessmen selling rifles to the Indians, cheating the army and anyone and everyone else. He gets into political trouble with the high command and the Grant administration and is court-martialed. But he talks himself back into command of the Seventh and rides off to glory. The end.

Okay. To begin with, this is a Warner Brothers bio-pic. They are not known for their veracity to actual facts. If you are casting Errol Flynn as anything other than heroic in 1941, someone would think you were off your rocker. It was intended to give Flynn yet another larger than life swashbuckling hero. I doubt historical veracity was on the agenda. And, Boots is actually one of whole slew patriotic films Warners made leading up to and around the time of America’s entry into World War II. Warners was the first studio to openly show their anti-fascist sentiments. While other majors – especially MGM – tended to go out of their way to not offend the Germans for fear of losing that market, Warners produced films like Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939,) The Sea Hawk (1940,) and Sergeant York (1941) which all have a direct, or heavily suggested anti-fascism bent. Yankee Doodle Dandy and Casablanca both 1942 would continue this trend. (All of the afore mentioned films, and Boots were productions under the hand of producer Hal Wallis.) They Died with Their Boots On doesn’t have a direct anti-fascism theme, does push forward an image of heroic leadership and self-sacrifice for the greater good. (Custer, in this iteration, rides into Little Big Horn knowing full well that it is a trap. And since he knew it was a trap, it really wasn’t a trap was it? He is doing it all to expose corruption. Anyway.) The only real villains in the movie are the corrupt Indian commissioner and greedy businessman who do anything to make a profit. So, are war profiteers the bad guys here? Custer may bravely fight the Indians, but here he is sympathetic and champions their nobility and unjust treatment. I told you it is highly fictionalized.

(A few bits: Only a few real historical characters are actually portrayed in the film outside of Custer and Libbie: Winfield Scott, Phil Sheridan, Ulysses S. Grant, and Crazy Horse – the only individualized Indian in the whole show. The year before Boots, the Warner Brothers film Santa Fe Trail (1940) directed by Michael Curtiz, starring our man Errol as J.E.B. Stuart and Ronald Reagan – wait for it, George Armstrong Custer – as Second Lieutenant, West Point grad buds assigned to a Kansas posting to have them end up tracking and fighting against John Brown band of fanatics. Fanatic – fascist. Incidently, Hal Wallis was involved as a producer on that pic also.)

Now all of this might sound as if I did not like They Died with Their Boots On, but not so. I think that it is a terrific movie. I’m a died in the wool Errol Flynn fan. The film is highly entertaining. The scenes between Flynn and Olivia de Havilland amusing and later touchingly effective. (Especially their final farewell.) The action scenes are dynamic and excitingly done. Raoul Walsh could direct great scenes between people and tough action scenes equally well. He is a director of huge versatility and quite underrated. One just needs to be aware that Boots is historical fiction to the nth degree.

There’s not much on the Custer front, although yes he pops up as a character, or an influence on the action, in any number of westerns, until the 1960s. The inept The Great Sioux Massacre (1965) and the wannabe epic Custer of the West (1967) make a blip on the radar screen. The former is a very made up, sloppy, poorly written, directed and acted (including favorites Joseph Cotton and Darren McGavin) is not really worth the time.

The latter, is also terrible, but worth a look. Custer of the West attempts to make a critical statement on American westward expansion, its politics and political corruption. Custer is again fighting corruption, again he is the brave officer and Indian fighter. He is also played by Robert Shaw (probably the best reason to watch this, although it is not one of his greater moments in film) with an odd accent. This is a would-be epic on a B+-movie budget filmed on the plains of Spain. (Insert joke.)

The great Robert Siodmak directed as if he did not know what to do with a 70mm camera. (Siodmak directed of the greatest film noirs: Phantom Lady, The Killers, Criss Cross.) It’s been too many years since I have seen it to comment much further. But it is a wreck, with a most strange Battle of the Little Bighorn I have ever remembered seeing – very formalistic, very European. Historically, it’s pretty much bull-shit.

There was a very short lived American television show Custer, also in 1967, recreating the fictional heroics in a hour-TV format for 17 episodes.

Which brings up to 1971 – thirty years on from 1941. War was again a major topic in American life, but not so much in a rah-rah kind of way. The American involvement in the Vietnam War is very much a socio-political hot potato at this time. In this atmosphere comes Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1971) based on Thomas Berger’s 1964 novel. (I will leave Berger’s novel aside, because the film lifts only a portion of the novel’s action/plot and uses it for its own purposes. I will only say, read the Thomas Berger novel – it is an American classic.)

The film tells the reminiscences of 121 year old Jack Crabb, who describes himself as the last only white survivor of the Little Bighorn. Jack relates his life’s tale into a bemused researcher’s tape recorder. This is a memory film, told from a viewpoint long removed from the events of the story. How reliable is the narrator? How accurate to history? Is it just a tall tale? (Much like Salieri in Peter Schaffer’s Amadeus, it’s what he remembers, not an accurate history, that’s the story) It is what Jack remembers of what happened.

Custer in this case is not the central character, but is a major supporting character that propels much of Jack’s eventual action and fate. Oh oh how the mighty have fallen from brave, courageous, and bold to a megalomaniacal lunatic in the person of actor Richard Mulligan.

The George Armstrong Custer in Little Big Man is vain, preening, megalomaniac twit utterly convinced of his own brilliance. He coldly slaughters a peaceful winter encampment of Cheyenne along the Washita River indiscriminately killing the elderly, women, and children along with warriors. There is nothing heroic, or admirable in this Custer. Convinced of his infallible brilliance and invincibility he later leads his men into the lion’s den along the Little Bighorn.

Little Big Man is a “revisionist” Western with Vietnam and U.S. transgressions very much on its mind. The Cheyenne in many ways are in the stead of the Vietnamese and their mistreatment and sometimes outright slaughter (My Lai was just three years previously) at the hands of U.S. forces. Most all of the white characters are either cruel, venal, corrupt, hypocritical, cowardly, dimwitted or a combination of any or all of these traits. Custer as I stated earlier is outright lunantic with delusions of grandeur. (That sounds kind of familiar to me.) The Indians, on the other hand, are mostly portrayed almost as flower children of nature – a very of the time sentiment. Neither of these views are accurate, but turnabout is fair game I guess. Two hundred plus years of often being portrayed as less than human savages, the American Indian is entitled to turn the tables on the paleface. But also, as I wrote earlier, this is a memory film of a 121 year old. And is he telling the truth?

Well I am not going to dissect Little Big Man here. I only wanted to briefly compare and contrast how a historical character’s reputation can vary wildly over time. Neither the Custer of They Died with Their Boots On, or the Custer of Little Big Man are anywhere near accurate But there are my two favorite versions, and pretty much diametrically opposed to one another.

I have to say that Little Big Man is among my favorite films. I saw it while still in high school, and it lead me to read and learn more about the myth and the reality of American history.

There haven’t been anymore “memorable” Custer portrayals since Richard Mulligan’s in Little Big Man. (Not for me anyway.) There was a television mini-series based on Evan Connell’s Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Big Horn in the 1990s with Gary Cole as Custer. I have not seen it since it was originally broadcast. My memory is that it was rather underwhelming. But there are many who disagree with me. Connell’s source work is such a rich and rewarding work, it would be quite difficult to match up to it. (It available to watch on YouTube if you have a mind to.)

Not too long ago I watched a 2007 BBC “documentary” about Custer’s ill fated final adventure. (There is a series of these BBC “Wild West” Re-creation-Documentaries available on YouTube.) While this piece contained a lot more detail of the political situation of the Crook & Terry expedition. I felt it still displayed Custer as a bit too damned attractive (even if over-confident.) And it spurred me to write this rambling mess. But this is not a “history lesson.”

This piece also a hellava lot longer than I intended. It is too long and yet not long enough to fully cover the subject. But I am going to leave it here. This whole idea of historical accuracy in dramatic movies is one that has always fascinated me. Does it really matter? The only answer I have is rather unsatisfactory – it all depends. Depends on what? That is for you to decide.

Leave a comment